Book Club – quirky critical and social justice takes on children’s literature. Otherwise known as what happens when someone interested in pop culture and political analysis has read the same bedtime story for the 100th time.

Richard Scarry’s Busytown has the most incompetent municipal government I’ve ever seen, despite the fact that I live very close to Washington D.C. The urban planning is an utter disaster, the roads make Beijing’s highways look orderly, and the safety standards and training are non-existant. Urban designers take note – except for its astonishingly resilient citizens, Busytown is everything you don’t want your city to be.

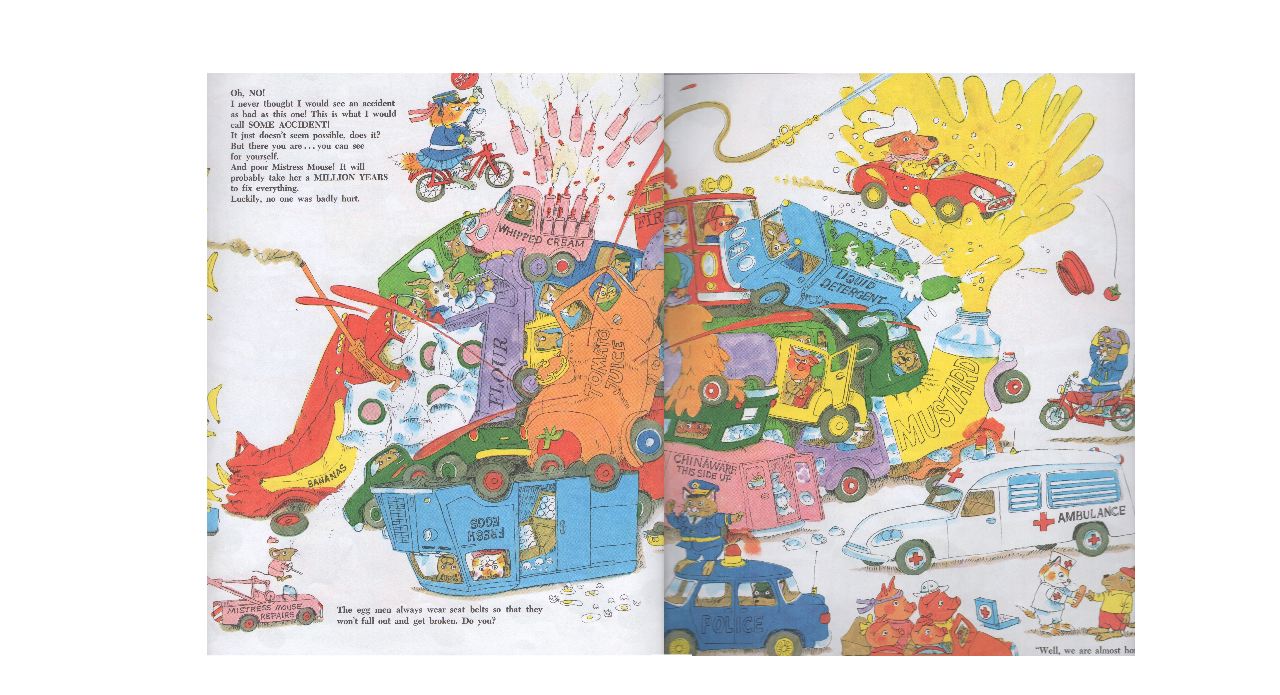

To start with, the city’s traffic patterns and the resulting crashes are atrocious. We have two Busytown books (Cars and Trucks and Things that Go and Lowly Worm’s Applecar), both of which feature multiple car crashes or near-misses. For example, one accident involves at least 17 different vehicles, including a squirting mustard truck, a chinaware truck, a flour truck, a whipped cream truck, a tomato juice truck, and an egg truck. While thankfully, “no one was badly hurt” but it will “probably take a Million Years” for the mechanic to fix everything.

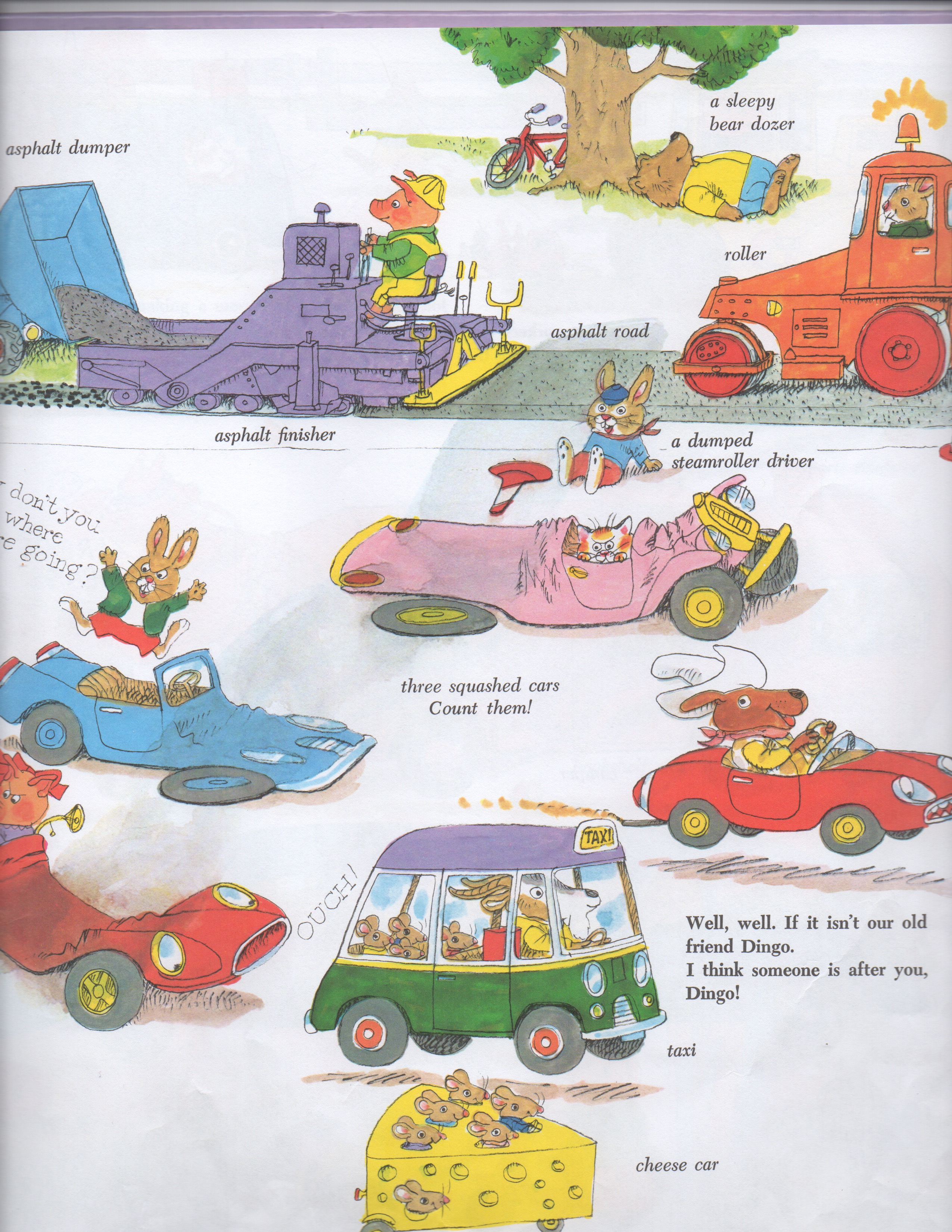

The roads all appear to be multi-lane with no actual stripes to distinguish between them. There are few or no traffic lights or stop signs, with individual police officers directing traffic at overcrowded intersections. There are multiple turn-offs with no merge lanes, like drive through hamburger stands on busy highways. The roads appear to be constantly under construction, with minimal markings and barriers. The roads themselves go through dangerous areas with a lack of supporting infrastructure, as “shortcuts through the mountains” result in dangerous falling rocks. (The roads also appear to cut right across ski trails, which can’t be safe for the skiers.)

Beyond the physical infrastructure, there is clearly little municipal support for regulation. Enforcement of traffic rules is minimal, with one clearly dangerous driver being pursued by a single (but very determined) bike cop in one book and another completely ignored in another. Vehicles vary in size from tiny pencil cars driven by mice to huge multi-story tourist buses. Many of them appear to not pass modern safety or emissions standards, including pickle and banana cars. One even transforms into a helicopter and balloon, while having no obvious method of propulsion.

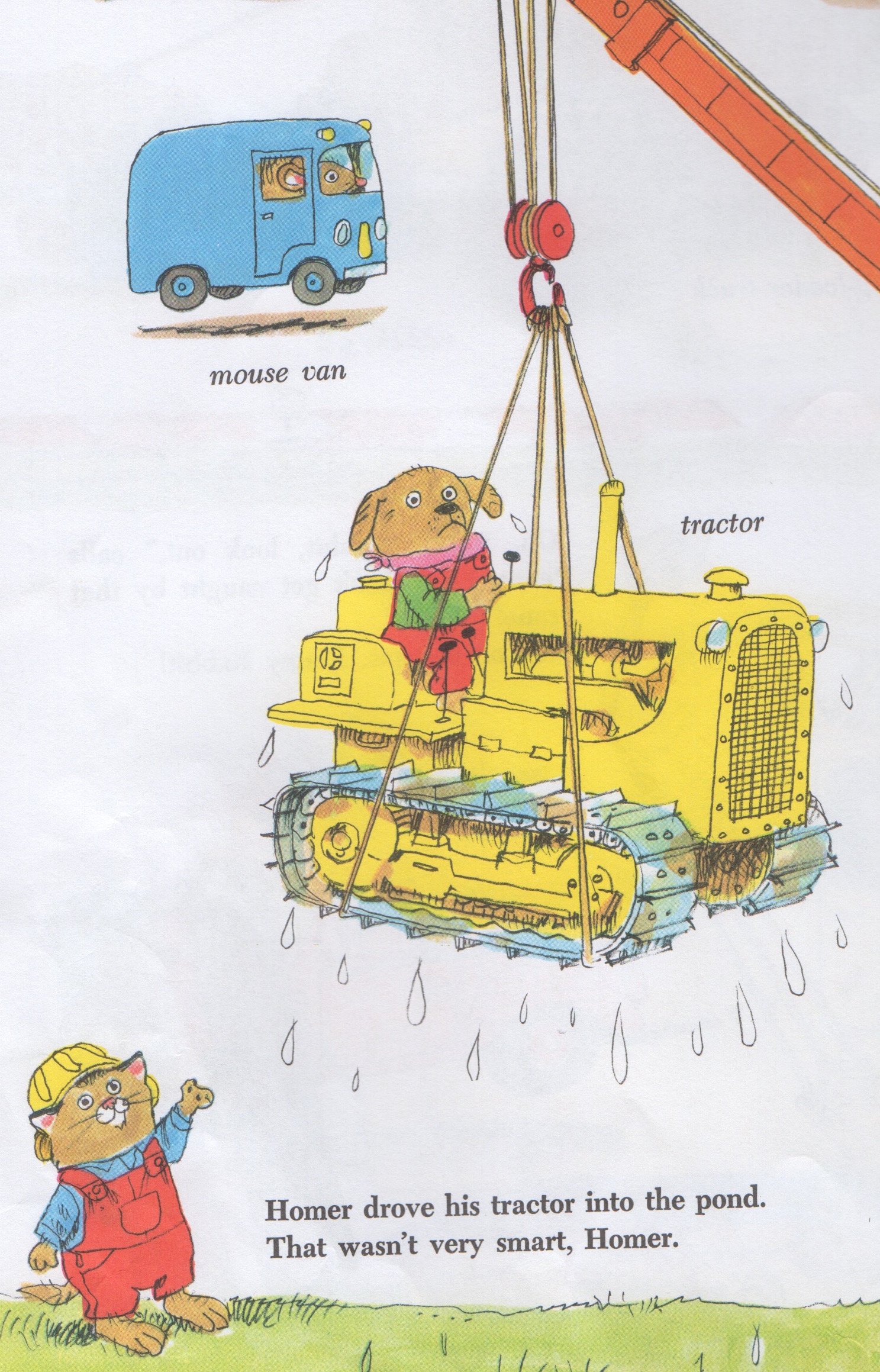

The complete disregard for safety extends to the municipal staff, who clearly need better training and performance standards. They make the beleaguered Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority look staggeringly competent. A crane driver steers straight into a lake. (That wasn’t very smart, indeed.)

A steamroll driver loses control of his truck, which runs over several cars. A car carrier operator drops a car into the ocean. Six different dump trucks in one area dump their loads at the same time because of vague misheard directions from a citizen.

Lastly, the city is extremely auto-centric. While it’s not safe for drivers, it’s disastrous for bicyclists and pedestrians. There are sidewalks, but cars veer onto them on a regular basis, knocking over parking meters. There are no bike lanes or separated paths. There is a police officer on a bicycle, but even she rides on sidewalks to avoid the multiple crashes. Instead of bicycles, even the children are gifted toy cars that they’re allowed to drive on the road!

While Busytown looks pro-urban upon first glance, it is a classic example of a poorly planned, shoddily managed semi-suburban area. It is certainly a product of the time. Parents interested in finding good neighborhoods for their children and city planners alike can learn from this disastrous mess.