Content warning: Racism, racially-based violence

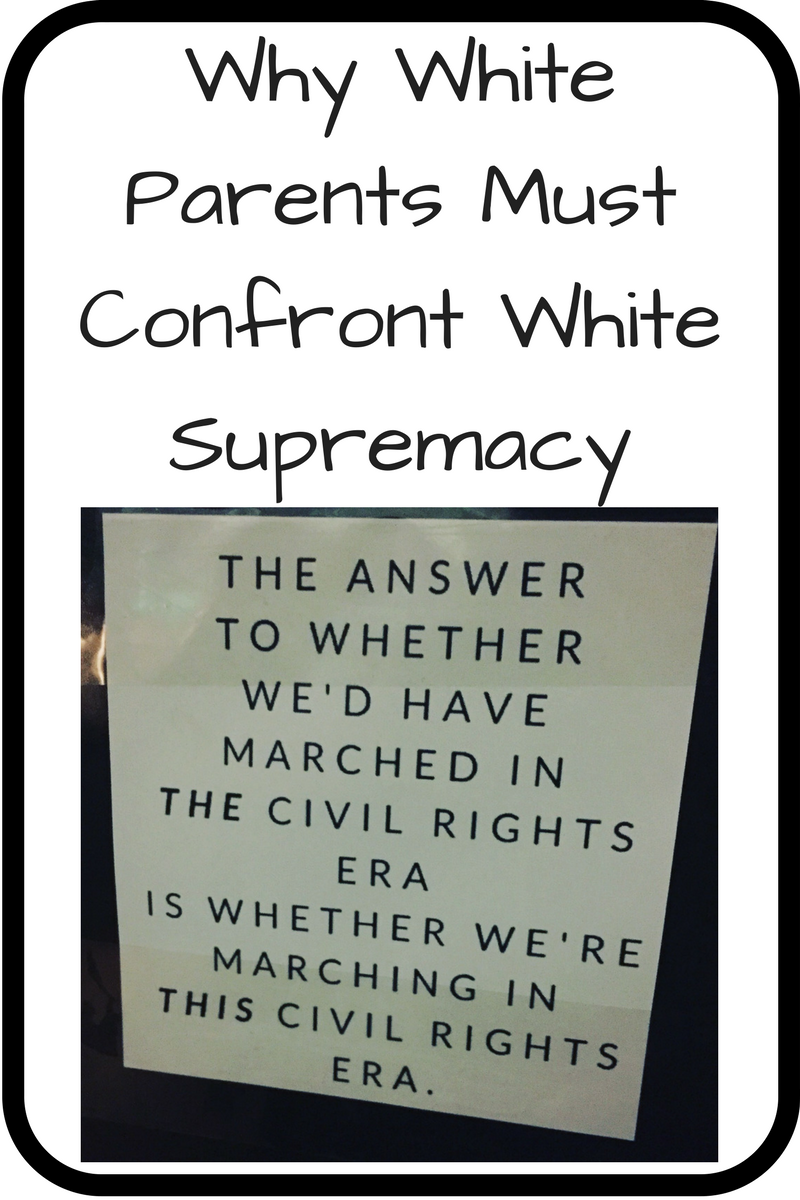

When I was a teenager in the late 1990s, I thought I was born in the wrong time. In my mind, I should have been coming of age in the 1960s, the height of the Civil Rights era. I imagined myself as a fierce crusader for the rights of others, on the front lines of the marches and sit-ins to confront white supremacy.

Dear Lord, I was a fool.

Admittedly, that’s pretty common among teenagers. But this was a special kind of foolishness. One that seems especially relevant in this rather terrible time in our nation’s history. Almost fifty years after Martin Luther King’s death, a white supremacist in Charlottesville plowed a car into a group of anti-racist protestors. He killed one person and injured 19 others.

To me, this incident highlights how ignorant I was back then. It also illustrates how common my views still are. My naivety illustrates everything about why white parents need to talk to their kids about white supremacy. (By which I don’t mean just Nazis, but the cultural aspect of valuing white people and culture above all others.)

The Civil Rights Era is Over, Right?

Back then, I thought the Civil Rights era was over. In my middle-class, 90% white suburban neighborhood, why wouldn’t I? In my mind, schools weren’t segregated (yes, they were and still are), black people weren’t discriminated against (yes, they are), and Jim Crow was over (the laws were – the effects weren’t). The 1960s marches and protests were over long before I was even born. The Rodney King beating and riots happened when I was eight. To me, there wasn’t anything else left to do.

Now I know better. Even before Donald Trump got elected, there was the shooting in Charleston, leaving nine black churchgoers dead. There was Michael Brown, Tamir Rice, and the many, many other unarmed black people killed by police. In protests against President Obama, there were explicitly racist signs with violent insinuations. During the lead-up to the election, the “alt-right” (modern-day white supremacists) moved from fringe things like Gamergate onto the national stage. White supremacy never left. Nothing should have been surprising about that weekend in Charlottesville.

And yet there were people who were surprised at the violence. Trump himself said we should condemn violence on both sides and there were “many fine people” who were marching in support of the Confederate statue. As if social justice activists are plowing cars into groups of peaceful protestors. I’ve moved on from my childhood innocence and naivety. So many others haven’t.

Protesting Isn’t Just a Parade

When I was in high school, I thought protesting was easy and fun. It’s just walking down a street with some signs, right?

I didn’t know about the fire hoses, tear gas and dogs they set on the Civil Rights protestors. I was ignorant about the people who got beat within an inch of their lives. People who got killed for speaking out besides Martin Luther King simply weren’t part of my education.

Since then, I’ve become an activist. There are times it’s good, when everyone is singing or chanting together.

But underlying it all, there’s always an unease. I know that depending on who I’m with and what kind of protest it is, the police could turn on us like they did in Ferguson. People who hate what we stand for could meet us with violence, as they did in Charlottesville.

You know what one of first thoughts in my head was when hearing about the car plowing into the crowd? “That could be me.” Not long after, it was “Oh, God, that could be my children.” Because I’ve been to protests and I’ve brought my children to them too.

As a teenager, I thought activism was just about marching, passing a couple laws, and going home.

But it’s much deeper than that. It requires a wholesale examination of our lives and power structures in our society. Racism is like a foundation made of rotting wood. You may fix one place, but unless you recognize that it’s rotten, the house is still going to fall apart.

Fighting for justice was and never will be fun or easy. It’s a long, hard, painful road.

While that knowledge makes it easy to say, “That’s too dangerous. I can’t expose my children to that kind of risk,” it’s a privilege to say that. The moms of black kids who worry if they’ll come home that night because of violent racists don’t have that privilege. The Jewish kids who overhear the anti-Semitic quotes from the alt-right don’t have that privilege.

How White People Can Confront White Supremacy

For those of us who have that privilege, we need to both look inward and outward. If we do nothing, we’re part of the problem.

The first step is to reflect on our own privilege, thinking about what we take for granted or don’t have to worry about because of our race. This may range from thinking about how the police treat us differently to how people don’t feel entitled to touch our hair. Extending that view to see how our influence ripples through our community, from our churches to our neighborhoods to our schools, opens up a whole world of understanding.

I’ve done some of that work, but certainly can always do more. A good place to start is signing up for the Raising an Advocate courses by Danielle Slaughter, who writes the blog Mamademics. Safety Pin Box, a subscription service for white allies, has a package specifically adapted for families.

Along with looking at our privilege, we need to educate our children. We’re in this mess in part because most white folks believed (and many still do) that if you teach children to be “color-blind,” we’d get rid of racism. That was tragically wrong. In fact, we’re seeing the results of it in the many young white people raising Confederate flags and supporting white supremacy today.

Conveniently, the resources above are specifically oriented towards parents so you can have these conversations! Other good resources include WeStories (a program out of St. Louis), A Striving Parent, EmbraceRace and Raising Race Conscious Children. The main thing is to actively talk to children about race so they can challenge racism as they encounter it in their own lives.

Next, you can stand up and take action. That might be challenging racist jokes or having the tough conversations at the Thanksgiving table. It may be pushing back on a friend’s questionable Facebook post. It may be painting over racist graffiti or attending a vigil against hatred. The Southern Poverty Law Center has a great guide on how to respond to hate in your community. (If you think there’s never been hate in your community, you aren’t paying enough attention.)

While there’s much more to do in terms of shifting power in society, interrogating the roles we hold and the roles our children are stepping into will get us much further than we are today. Even if you take more immediate action, that reflection is an essential step. Otherwise, we’ll just be finding more ways to repeat the mistakes of the past.

In the past, I’ve also written about how I’ve come to understand my white privilege and confronted my own racism. For ongoing conversation on the topic and parenting in general, follow us on Facebook.