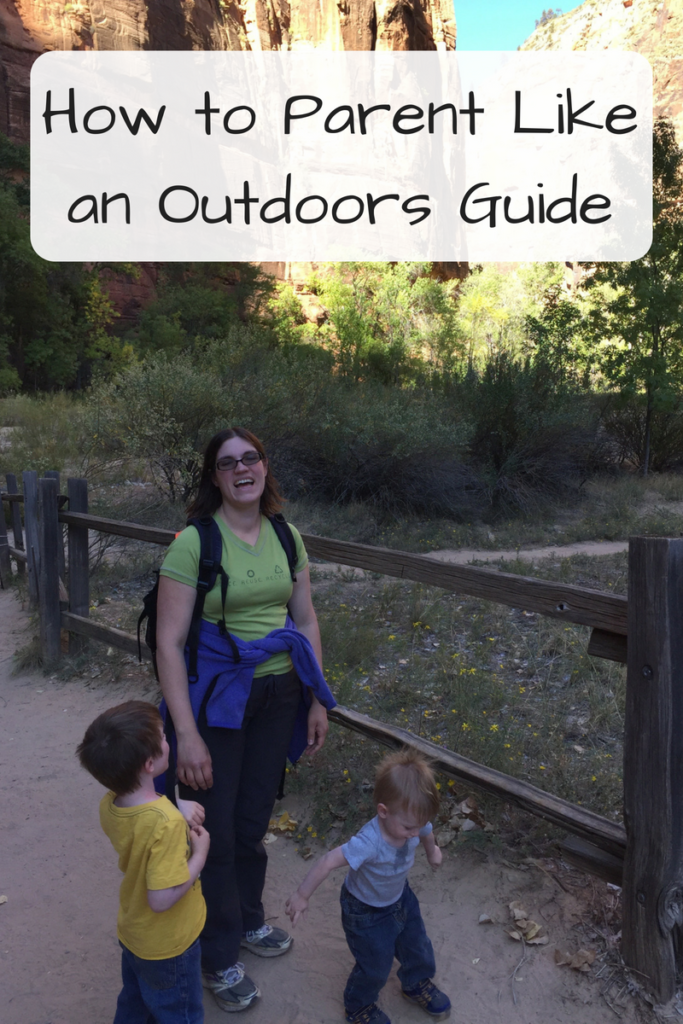

Watching my five-year-old run down a rocky hiking path, I winced. I wanted to say “Be careful!” so badly. But I thought for a second and tweaked it just a bit.

“If you run, you’ll hit loose rocks,” I yelled. “If you don’t like walking down, you can walk sideways, like this,” I added, demonstrating the sidestepping technique.

He slowed down and started walking instead. “But it’s faster to run!” he explained as I caught up to him.

“I know, but you know what happens if you hit a loose rock? Bump bump bump bump,” I said, illustrating the bouncing down a trail with my hand. “That would hurt.”

While I’m not as outdoorsy as some (like these folks who hiked the Grand Canyon with their three-year-old), we’ve brought our little ones on their fair share of outdoors adventures. While I think just being outdoors teaches kids amazing lessons, parenting in the wild has helped me a lot as a mom. Because helicopter parenting is far too restrictive and totally free-range is a little too hands-off, I’m somewhere in-between.

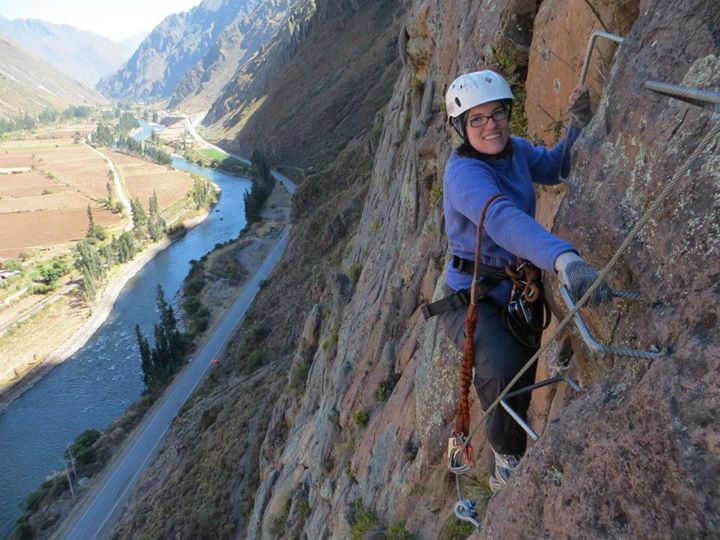

Instead, I see myself in the role of parent as an outdoor guide, like one you have for hiking or rock-climbing. Although I’ve never been a fully licensed guide, I’ve led hikes, belayed climbers on rock-climbing walls, and taught field ecology to elementary and junior high students. You have to be quick-witted, skilled at the Art of Being Prepared for Anything, and well-versed in both first-aid and outdoors skills. Most importantly, you want to bring people on and back from an adventure safely, where they both learn skills and a lot about themselves.

Here’s what I learned that applied to parenting:

1) Being strong, smart and flexible at the same time.

Some people – usually men who like weightlifting – think rock-climbing is about doing a series of pull-ups. Invariably, they are exhausted by the second climb. In contrast, the strategic climber who uses their legs well is just getting warmed up. While strength is necessary in both climbing and parenting, it’s not enough by itself. It needs to be tempered with a thoughtful investigation of the unique situation, as well as the ability to switch gears as needed. The ability to judge which routes or fights are worth pursuing and which are best just to leave well-enough alone for now is key to reducing stress. Toddlers and climbing walls will always be the ones to win pure power struggles.

2) Evaluating risk and teaching those skills to others.

On an outdoors trip, you have to trust the people you’re guiding not to do anything stupid. Part of building that trust is teaching them the difference between what will get them in big trouble and what’s a reasonable risk, especially when it’s not obvious to a newbie. The level of risk also depends on the circumstance – in some places, you’ll be fine hanging your food from a low tree branch but in others you better put in it a bear canister if you don’t want a furry friend in the middle of the night.

Teaching children to judge and minimize risk without eliminating it is even more important. Whether making friends with a new person, climbing up a slide, or going to sleep-away camp, childhood has an immense number of social and physical risks. But avoiding them altogether limits opportunities, the ability to meet new people and find adventure. It’s tempting to make those decisions for your kid, but teaching them to make those decisions independently is even more important.

3) Being able to judge when to spot, when to belay and when kids can go on their own.

While I’m not a helicopter parent, there are definitely times I hover, especially when my kids are climbing a piece of playground equipment they’re not steady on yet. But I don’t see this as a bad thing; it’s the exact same thing I would do if my husband was tackling a tough bouldering problem.

Spotting – putting yourself between the climber and the ground as a backup to falling – is a perfectly valid strategy when someone needs that extra level of protection. Similarly, belaying – when you’re hooked in to a rope to prevent falling – is appropriate when you’re high up enough that you could get seriously hurt from a fall.

Figuring out when to provide full, partial or no protection for your child when they take a risk is the next step after teaching how to judge one. Taking a huge risk with no safety net is terrifying; taking a little one is fine. On the other hand, always being on a rope can encourage recklessness. Figuring out how to offer that support is another balancing act.

4) Helping them set their own goals, while also giving input when needed.

A good outdoors guiding company will focus on the participants’ goals, whether that’s climbing a huge mountain or backpacking for the first time. At the same time, they’ll also let you know if you simply aren’t ready to take that step yet. Someone who has never put on crampons shouldn’t try to summit Mt. Everest.

As a parent, I want to encourage my kids in their goals while also making them aware of the hard work that has to happen to get to them. In a few circumstances, I may even recommend they has a back-up plan in case things don’t work out. Even the most prepared, experienced climber shouldn’t summit Everest if there’s a storm coming.

5) Recognizing and respecting how your children’s skills are different from your own.

One of the worst things on a hike is when you’re the last person in the group, trying to keep up desperately. As soon as you get to the place where everyone else is resting, they get up and start again. Conversely, one of the hardest things as a guide is keeping track of where people are and ensuring you’re going their preferred pace, not yours.

Understanding and respecting how your children’s skills are different from yours and how that may affect their goals, interests, decisions and activities will help you give them the freedom they need. Really listening to them is key. Understanding that not everyone wants the typically college-career-married life path can help us embrace whatever journey our kids set off on.

6) Encouraging failure as a form of learning.

You can never get better at rock climbing without falling a few (if not several) times. You don’t learn to put up a tent without getting tangled in poles once or twice. Anything worth doing involves screwing up and learning from it before getting it right. Our current test-based society is a little obsessed with getting things right the first time, but that just leads to depressingly stunted thinking.

7) Travel light.

Even if you’re car camping, packing too much is a big pain. When you’re backpacking, it becomes sheer misery.

The same goes for raising kids. Having too much junk makes parents and kids less, not more, happy. One of my favorite parenting books is Simplicity Parenting, which among other things, advocates having fewer, more versatile, and more simple toys.

For our sanity, pocketbooks and environmental / social sustainability, we try to limit the sheer number of toys (and other stuff) in our house, particularly the number that require batteries. We also try to buy ones that our kids can use in different ways as they get older, so they’re less likely to get bored of them. Most importantly, we try to emphasize time spent together over physical things.

8) Spend as much time outside as you can.

While being outdoors benefits everyone, it’s especially important to children’s development. Richard Louv’s book Last Child in the Woods talks about “Nature Deficit Disorder,” which happens simply when kids are inside too much. There’s some proof that being inside too much can stunt your immune system and increase the chances of depression and anxiety.

While being outdoors benefits everyone, it’s especially important to children’s development. Richard Louv’s book Last Child in the Woods talks about “Nature Deficit Disorder,” which happens simply when kids are inside too much. There’s some proof that being inside too much can stunt your immune system and increase the chances of depression and anxiety.

9) Teaching appreciation of diversity, both of people and the natural world.

The best outdoor guides know all about the natural and human history of the places they lead people. Listening to a guide or park ranger explain the details of places I’m visiting has expanded my enjoyment of those places so much. Their inherent enthusiasm for the subject inspired excitement in me.

Likewise, I’d like to pass on that knowledge, love of learning and appreciation of diversity to my children. You miss out on so much beauty if you just stick to things you already know. I want them to explore while also appreciating the simple pleasures around them.

10) Respect your fellow travelers and the environment.

Leave No Trace is a popular camping and hiking philosophy. While it’s impossible to leave zero trace, the idea of leaving a place better than when you started is a good one. Two of the biggest values I want to teach my kids are kindness and respect. Those are as helpful in everyday life as they are on the trail.

11) Fight for the things you love.

The first people to advocate for environmental protections were people who loved both the outdoors and bringing others into it, like John Muir. While there were some definite problems with the original conservationist movement (mainly racism and classism), we can still take inspiration from the idea of our passion motivating us to make a difference. Whether it’s working to ensure everyone has access to fresh, affordable, good food or protecting clean water, advocacy starts with a love of people and nature.

12) Remember that it’s about having fun.

In the middle of a downpour or a temper tantrum, it’s hard to remember that this experience is supposed to be fun. But that’s a major reason I became a parent. And despite all of the challenging times so far, I truly enjoy so much of the time I spend with my kids. If we can’t stop and just enjoy ourselves with our kids – finding the magic in the mess, as Beth Woosley puts it – we’ve missed much of the point.

For more on positive parenting, check out 50+ Awesome Acts of Kindness for Kids and Families.

Want to participate in our Family Kindness Challenge? Sign up for our newsletter and get five days of activities to do with your kids that help teach kindness, tolerance, and empathy.

Pingback: This week in the Slacktiverse, October 13th, 2015 | The Slacktiverse

Pingback: The Best of 2015 | We'll Eat You Up – We Love You So

Pingback: Encouraging Exploration: A Parenting Philosophy | We'll Eat You Up – We Love You So