The exact numbers weren’t easy to read, but the graph lines showing the poll results were clear – the majority of the folks at the public meeting were white. Looking around the packed high school cafeteria confirmed that fact.

My mind returned to the graph we had seen a few moments earlier. In bright colors, it laid out the racial make-up of the students in my kids’ school district: 28% white, 31% Hispanic, 22% Black, 15% Asian, and 5% “other.”

Hmmmm.

Similarly, a later poll showed that the majority of people were from a community far south of the meeting – 45 minutes without traffic, even more with traffic on a weekday evening. (There were two public meetings earlier in the week that were far closer and more accessible for that community. All three meetings had sign-ups that filled almost immediately.) Knowing the wealth of that community and the socioeconomic statistics of the whole district (44% of kids have qualified for free and reduced lunch at some point), I knew if we had a poll about socioeconomic status, we would see similar disparities between who was in the room and the district’s overall population.

Something was definitely amiss.

In theory, everyone in that cafeteria was there for the same reason – because we care about our kids’ education. But when we got down to the nitty-gritty, different people defined “caring about our kids’ education” in very different ways.

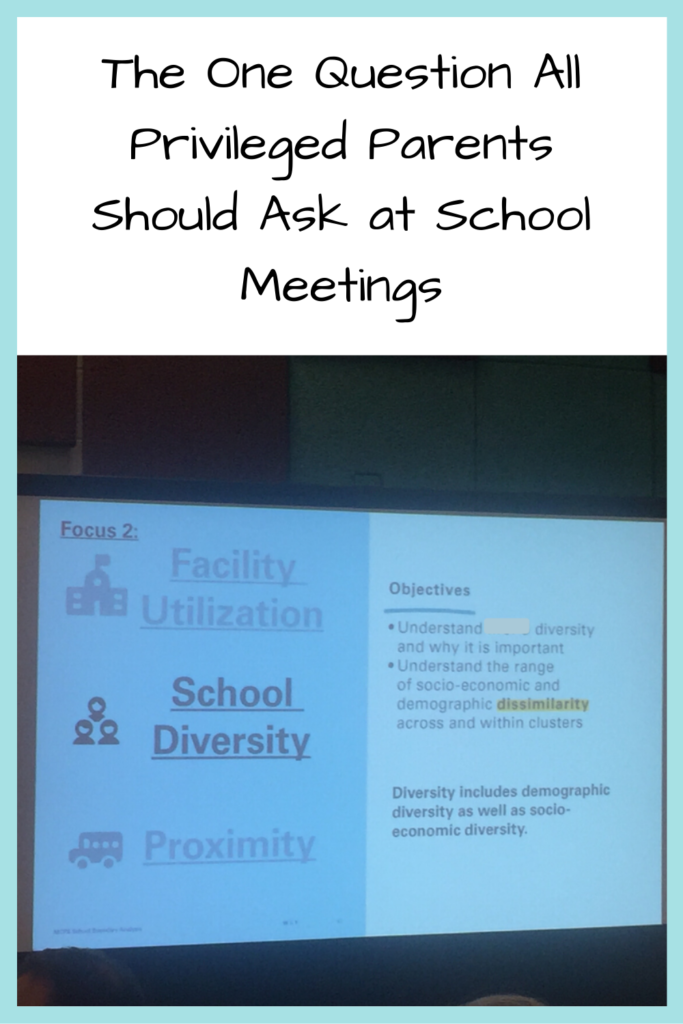

Just for context, our district has serious problems with utilization (how full or empty schools are), diversity (socioeconomic, racial, and otherwise), and proximity (how close a school is to a child’s house). Some schools have way too many kids, while others have a lot of empty seats. The socioeconomic and racial disparities are significant enough that the local news has covered them multiple times.

The district was running the public meetings to collect data. Consultants would use that data to help the district decide whether or not to shift the boundary lines between schools. It wasn’t even about determining new lines. In theory, the analysis should collect the data that would allow the district to think about the best ways to even out the number of kids in each school, have schools be ethnically and socioeconomically diverse, and help as many kids as possible go to schools close to their homes.

Sounds reasonable, right?

Not to the majority of people in the room. In one poll, the vast majority of people vehemently disagreed that rewriting boundaries should even “occasionally” be considered, despite the inequalities the district faces. Attendees against the very idea of the analysis constantly interrupted the speakers. They yelled and demanded their “questions” be answered before the presenter even got to speak. One person actually asked, “I know you talk about the benefits of diversity, but have you considered the drawbacks?” Another tried to yank the mic out of a facilitator’s hand and scratched her. A third threatened to sue them. (On what legal basis? Who knows?) In a different public meeting, a recent high school alumni spoke about how he benefitted from diversity; people actually booed him.

Mind you, this is an area that considers itself progressive and liberal. Yet the voice of this one particular group swamped the meetings and overwhelmed every other perspective.

The fact is, my school district isn’t unique in these issues. Schools all over the country have huge inequality issues and people pushing back against fixing them. These people say they want what’s “best” for their kids – no matter what the effect is on anyone else.

This self-focus is reflected in kids’ attitudes too. In a 2014 nationwide survey by the Making Caring Common project by Harvard University, 48% of young people said their parents cared more about their achievement than their happiness or if they helped others. Ouch.

Even if parents don’t want to send these messages, they are with this type of behavior. And kids are hearing them.

But against this narrow point of view pushed by some of the most privileged people in a community, what can we do?

At the public meeting, I put in my two cents during our tabletop discussions and tried to make my comments as useful and productive as possible. During the question and answer session, I listened to person after person lodge a complaint rather than a question. I wanted to say something to counter the endless pushback, but struggled to think of a legitimate question.

Finally, I realized the question that no one was asking: “How will we get the input of the people who are currently underrepresented in these discussions? Who haven’t been able to come to these meetings?” Unfortunately, the Q&A time ended before they got to me.

Because no matter what I personally have to say, I need to ask that question. I’m still coming at it from my privileged background and standing. I don’t have the lived experience of the folks who are most affected by the inequalities.

In these situations in the future, I’m going to try to ask “Who is at the table and who isn’t?” To encourage the system to seek out the input and opinions of underrepresented groups. To find out what the opinions are of those folks and support and amplify them. As a person of privilege, this is my responsibility and obligation. We all need to ask different variations on this question as appropriate.

We can’t model true kindness for our kids unless we demonstrate it ourselves. That begins with ensuring everyone’s voice is heard at the table.

For more on social justice and parenting, follow us on Facebook!