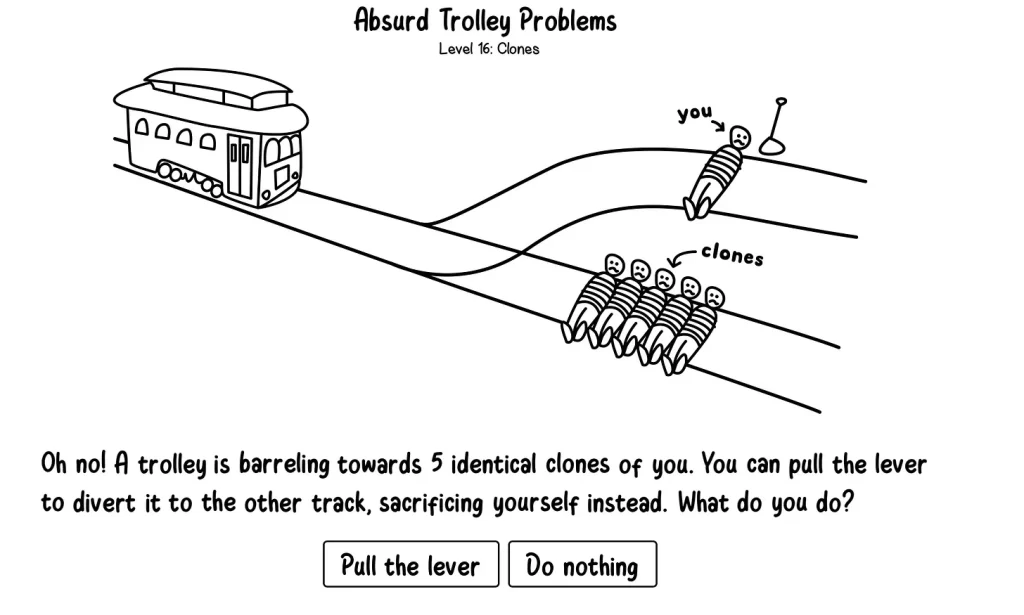

The computer screen showed a line drawing of the classic philosophical thought experiment called The Trolley Problem. Except instead of stick figure people tied to the railroad tracks like in the original version – which asks you to decide whether to redirect the trolley and save the 5 people on the tracks but kill a single person on the alternate track – it was a choice between you and five identical clones of you.

I raised an eyebrow. “That’s an interesting twist,” I commented to my older son, who was both laughing and seriously contemplating the moral implications of this ridiculous choice. It was one of a series of increasingly silly versions of the problem that he was futzing around with. I pointed out, “You know, a lot of people think the original version is silly too because it only offers those two awful choices. Which is true. I guess the thing is that it makes us think about who gets hurt in the decisions we make.”

While the trolley problem itself is ridiculous, there are plenty of versions of it in our society, like people who posit that we have to trade off between environmental protection and the economy. Or posit that to have a good life, we have to screw over Amazon workers so we can have overnight delivery. (In fact, one of the versions says “A trolley is heading towards one guy. You can pull the lever to divert it to the other track, but then your Amazon package will be late. What do you do?”) Or that we don’t have an obligation to pay school taxes over a certain age because well, that’s not *our* responsibility. At that point, society is not even presenting us with an impossible choice – it’s saying that we don’t have to care at all. After all, it’s not our responsibility if the trolley is going to run someone over.

Except it is.

It’s our responsibility to stop the trolley and buck this thinking altogether. My kid and I talked about if it’s possible to find a third option that offers creative, just solutions instead the two impossible options of the trolley problem. Instead of throwing the switch to run people over, we can find a way it doesn’t exist at all.

Or as writer adrienne maree brown said in a Facebook post:

you tell me this is all

this is the way it goes

these are the only options

this is who gets to live

this is who gets to love

this is who gets to parent

this is all the safety we can muster

this is where we will settle

and this is what a life costs

and this is how humans are

but my love

this is only as far as they could go

i promise

as i practice

we can imagine more

Of course, with my older kid, any discussion ended up somehow being about animals. (One of the versions of the problem in the game had 5 lobsters on one track and a cat on the other.) He holds rabbits in especially high regard, but values almost all animals. Some days, he likes them much more than people.

I asked him how he would weigh the value of some animals against others. After some contemplation, he declared that he thought a single ant was less important than a single rabbit because there are more ants than rabbits and in the context of an ant colony, there are many that could replace it. I smiled because his reason was completely different from what I – and most philosophers – think of! While I was basing the value judgment on intelligence, type of animal (mammal vs. insect), or capacity to have something resembling human feelings, he considered the question in the context of the larger community. He thought of the unique (or not so unique) role of the individual in the greater whole. It’s times like those where I actually feel a bit like “It’s sinking in! All of these discussions about right and wrong are sinking in! And he’s thinking of things totally different than I am and still so valid. Hallelujah!”

While we were on the subject, I really wanted to hear his thinking on a different thought experiment that presents another absurdly impossible choice. One of the other classic questions is, “If you could go back in time and kill baby Hitler, would you do it?” No one wants to kill a baby, but Hitler! Contemplating this version, he said that instead of killing Hitler, he would drop him off in the jungle to be raised by monkeys and become Tarzan. I don’t know about the practicality of that solution, but I suppose if you have a time machine, anything is possible. I appreciated that he was again able to find a compassionate solution that totally side-stepped the false choice.

Admittedly, not every kid will be entertained by a virtual version of a philosophy lesson, no matter how silly it is. But there are lots of inroads to conversation. For example, Undertale is one of my favorite video games. The entire point of the game is to question the traditional video game quest where you go through and kill all the monsters. It’s very silly and funny and has eight-bit graphics and plays with some hard-core philosophical questions. Heck, even the Dogman graphic novel series brings up questions of whether people can move past their generational curses and find redemption for terrible things they’ve done. (There’s a reason one of the book titles is a play off of Crime and Punishment.) There are opportunities for these conversations everywhere.

We face impossible choices every day and yet need to look past them to find the alternatives. To consider the value of everyone involved and to teach our kids to do the same. That’s the only way we’ll ever build a world that isn’t based on a series of metaphorical trolley problems.

If you want to try an increasingly ridiculous number of philosophical conundrums, this is the version he was playing with. Let me know your thoughts about it, especially if you play it with your kids!