“What’s that road named after?” my older son said, pointing to the road that his elementary school is named after. He was in his “asking questions about why things are named what they are” stage.

“I don’t know,” I said. “We can look it up.”

That’s how we found out his elementary school is named after an enslaver.

In some ways, it’s not surprising if you know much about the history of my area. Maryland was part of the North in the Civil War, but not out of choice. In fact, it held on to the horrifying institution of slavery after the Emancipation Proclamation, which only covered the states that seceded. As main roads are often named after rich, powerful people, it makes sense that the road would be named after the richest person in town – who held slaves.

Nonetheless, I was horrified.

The only thing I knew about the person previously was that his house was used as the headquarters for the local historical society. I never would have thought twice about the road name if my older son hadn’t asked that question.

I was glad he did though. Even if the person the street was named after isn’t someone we would valorize now, it’s someone the people in charge of name streets did valorize back then. We need to acknowledge the brutal truth of that fact.

When I explained it to the kids, I said that it was named after someone who was rich and important in the town and he owned enslaved people. Simple as that.

Thankfully, there are places of honor in our city for the flip side as well – people who fought for civil rights. In particular, there are two beautiful memorials for William B. Gibbs. He was a Black schoolteacher who realized he was making half the salary of the white teachers in the county. He brought his case to the NAACP. They brought it to the courts with Thurgood Marshall representing the case. Later on, Marshall led desegregation of schools through Brown vs. the Board of Education and became the first Black Supreme Court justice.

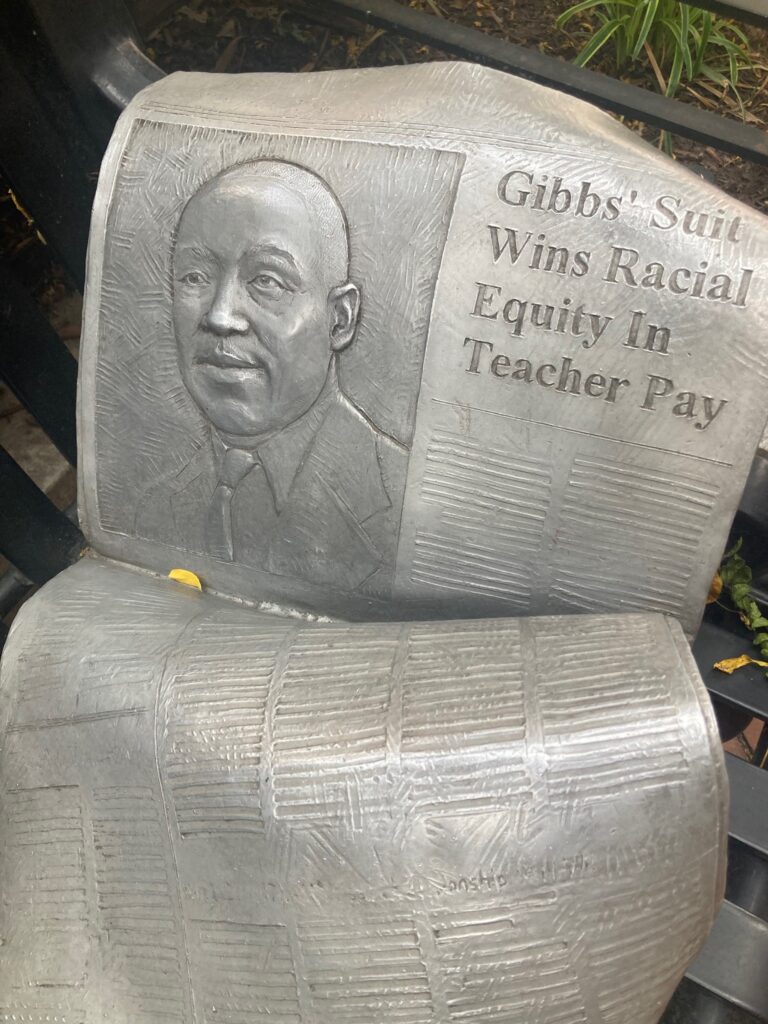

One of the monuments to Gibbs is large and hard-to-miss – you literally walk under it on the way to the parking lot. The other is more subtle, but puts you more in the moment, in my opinion. It’s a metal statue of a newspaper that’s on a real-life bench, with the headline of “Gibbs Wins Racial Equity in Teacher’s Pay” splashed across the top.

These monuments present great opportunities for discussion as well. After our city’s Juneteenth celebration, my younger son and I walked over to the smaller memorial and sat on the bench next to it. We talked about how the situation was terribly unfair and how Gibbs stood up to it.

Talking about the people who took a stand in our city and sometimes even our neighborhood provides a bit more intimacy and closeness to history than we might have otherwise. Just thinking about the fact that this person stood where we go all the time brings you a little closer to them. It helps you think about what you might have done if you lived here at that time.

While you won’t have the same street names or monuments in your city, I’m sure there are traces of local history if you look. There are opportunities to talk about these “difficult” subjects to kids all around us, as long as you are willing to tell the truth.