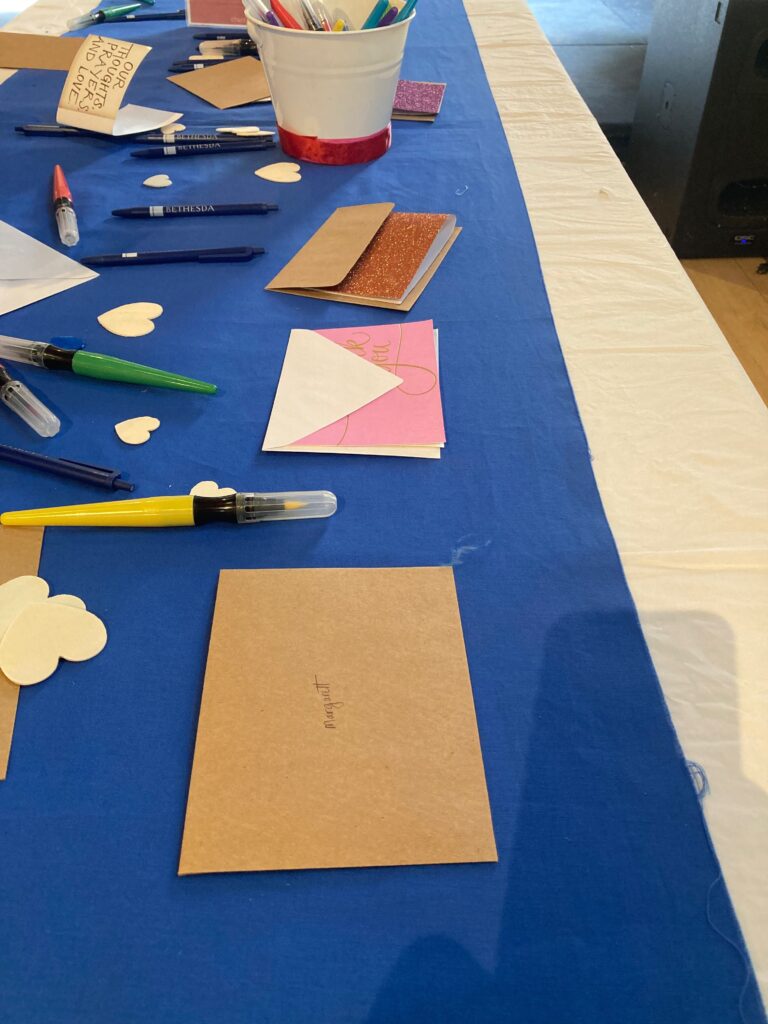

“Remember Ms. Margarett from church? She’s in that picture,” I said to my younger son, pointing at a photo of her and her husband. “She’s had cancer for a long time and she’s at the point where the treatment isn’t doing much and is making her feel worse. So she’s stopping treatment. But that means that she’ll die soon. They’re just trying to make her as comfortable as possible and we’re making cards about peace and love. But like, we can’t say get well soon or anything like that. Because she won’t.”

“Hm,” he said, contemplating the situation. He started drawing an elephant.

When he had drawn a glorious elephant, he asked, “Can you write that?”

“The peace and love part?”

“Yeah. Say ‘This is a love elephant.’”

Even though he’s only seven years old and hasn’t had a lot of experience with death, it’s not a foreign concept to him. Heck, we have a cemetary just beyond our backyard. (And not a small one, either.) We’ve talked to our kids since they were very little about death, both the biological reality and the fact that different people have different beliefs about what happens afterwards.

But I do think that this is the first time he ever had to think about the process of dying. Most of the time, death is either fictionalized – like the constant danger in fantasy stories like Doctor Who – or far away. When my grandmother died, he had never met her. She was a vague person who was Nana’s (my mom) mom. He may have thought of the fact that us or him will die some day, but it’s always in the far future. Not the now. Not someone he’s met.

But now the process of dying was very much staring us in the face. A long-time member of our church had announced that his wife was going into hospice after a long series of illnesses. We’ve been going to this church for 15 years and I never remembered a time that she wasn’t terribly sick. While it was sad, I could also see how deciding to stop treatment would be a relief after so many side effects and so much pain.

So now I was trying to explain hospice to a child. A kid understands “get well soon” cards. But how could I explain someone choosing to die instead of continuing treatment?

As it turned out, my explanation seemed to be good enough. He sort of nodded, drew his elephant, and moved on. My older son drew a similarly thoughtful card featuring a rabbit, his favorite animal. When we found out that Margarett had died only a little while later, both kids understood why it was sad but also were able to process it.

Often, these hard, complex subjects aren’t as hard as we as parents work them up to be in our heads. The straightforward, honest explanation is usually the best one.

The good thing is that we don’t have to have these conversations or deal with these difficult situations alone. We can do it in community. In fact, community both provides us with more chances to have these conversations and the relationships to deal with them. Our church providing the chance for all of us to write these cards of comfort showed my children that this topic wasn’t something to shy away from. Instead, it was a moment to come together to provide her and her husband with the emotional support they needed. And it was a task for everyone – not just the adults.

The places and people we bring our children into will shape them. We can’t hide our kids away from society and the problems that come with it. But if we can find the right communities, the people around us can provide what we and our children need to move and learn and grow.